Blogs

6 Devastating Coal Mine Accidents Throughout History and Lessons Learned

August 21, 2023

Coal mine accidents can be devastating to operations and the lives of miners. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics places underground mining among the top ten most dangerous jobs in America. Out of approximately 66,000 miners, 10 died in 2022, according to the bureau’s annual statistics on how many people have been killed in coal mining accidents.

Methane and other flammable or toxic gasses are a fact of life, and of death, in coal mines. Explosions caused by gas are the most common cause of these disasters. Methane explosions can ignite even more powerful coal dust explosions. The worst Kentucky coal mine accident, for example, was a methane gas explosion that killed 62 miners in 1917. Coal mines can simply start burning with fires that can be extremely difficult to extinguish, such as an 1869 fire in the Avondale mine, which killed 110 workers and rescuers.

In any of these events, trapped miners can be killed by the explosion, the resultant fire, or smoke that fills the chamber. In poorly ventilated mines, miners have died of gas inhalation absent any explosions.

The coal mine roof or ribs (mine walls) can collapse, trapping miners. Equipment can fail with deadly consequences. Some of the worst situations have been caused by mines flooding and drowning workers and the failure of wastewater retention and tailings dams, sending toxic liquid mine waste rampaging through downstream communities and ecosystems.

Coal mine accidents come in a variety of shapes and sizes. Many factors can contribute to lives lost and suspended operations. These 6 coal mining accidents are some of the worst in recorded history, but they provide an excellent opportunity to learn from past mistakes and improve modern site safety.

Liaoning Province, China

The 1942 Benxihu Colliery Disaster is considered the most deadly coal mine accident in history, taking the lives of 1,549 miners.

The Benxihu Colliery (a colliery is a coal mine and its associated structures) was first opened in 1905 as a joint Japanese and Chinese venture and is also referred to as the Honkeiko coal mine, its Japanese name. During the Sino-Japanese War, the mine fell under full control of the Japanese military, which led to poor working conditions.

On April 26, 1942, an explosion of gas and coal dust sent flames and smoke shooting out of the mine shaft entrance. The authorities decided to seal the mine’s pit head to cut off oxygen to the fire, trapping more than 1,500 miners underground with nothing to breathe but smoke. Relatives who had rushed to the site found it cordoned off by the military authorities in charge. The reclamation of human remains took ten days to complete.

The mine continued to operate through the end of the war, making study of the incident difficult. After the war ended, an investigation by the Soviet Union laid the death toll squarely on the decision to seal the mine. Nearly all the workers died from smoke inhalation, not from the explosion or fire.

As a result of the Benxihu Colliery Disaster, some of the major reforms implemented by the mining industry in China included improved ventilation systems, the installation of dust suppression systems, and the mandatory use of safety lamps.

Courrières, France

The March 10, 1906, Courrières Mine Disaster was a gas explosion. It was the world’s second-deadliest coal mine catastrophe and the worst in Europe’s history. The confirmed death toll is 1,099 miners.

In its day, the Courrières Mine was an exceptionally complex structure with multiple underground levels connected to multiple pit heads above. It was thought, or claimed, that connected spaces would make for better rescue conditions and make coal easier to transport. It apparently gave the explosion more room to travel and more debris to be cleared by rescuers.

Two prevailing theories were considered: either an accident in the handling of mining explosives; or, the “naked flame” of a miner’s open lamp ignited available methane gas. More expensive enclosed Geordie or Davy lamps, then available for almost a century in mining, were not provided to the Courrières miners. Frederic Delafond, the Director of Mines, excused the lack of a clear determination of cause:

“This is what generally happens in catastrophes where all the witnesses to the accident are gone.”

Not all. About 500 miners escaped immediately, and 14 more were rescued within three weeks, saved by their own heroic survival decisions. Although no official final cause was reported, the residents in the affected mining towns pointed to the mine operators. Around the time the funerals began, public anger at Compagnie des mines de Courrières led to a series of strikes, eventually reaching 46,000 strikers.

Völklingen, Germany

The Luisenthal Mine had always been problematical due to high concentrations of “firedamp,” essentially any flammable coal mine gas. In roughly the first half of the 1900s, there were 20 explosions or fires in the mine. After an explosion in 1941 killed 41 miners, the mine was equipped with the latest in mine safety technology. The mine even won an award for its safety standards.

This did not prevent another coal mine accident.

On Sunday morning, Oct. 7, 1962, at about 7:45, a “vague bang” was heard throughout the area as a gas explosion rumbled through the mine. A cavern containing methane had been opened, and the resulting methane explosion triggered an even more massive coal dust explosion. The mineshaft was almost 2,000’ (600 m) deep, yet the explosion was strong enough to blow the manhole cover off the shaft into the scaffolding above. Out of a reported 433 miners present, the blast killed 299 and injured 73. It is still the region’s worst coal mine accident.

It was never definitively determined what sparked the initial explosion. Speculation at the time was a defective lamp or illegal smoking; several cigarette butts were found. In 2005 the mine was permanently closed. A memorial of 299 stones is dedicated to the lost miners.

Buffalo Creek Hollow, West Virginia

The Buffalo Creek Flood disaster occurred on February 26, 1972, when three impoundment dams on Buffalo Creek holding coal mining wastewater from the Buffalo Mining Company collapsed, one into the next, like dominoes.

Dam #3, the uppermost, went first. It had been built out of poorly selected mine waste and on coal slurry, not bedrock. Dam #3 had long exhibited problems, and in 1970 the state recommended an emergency spillway be built, which never happened. The mine operators assertively ignored federal regulations as well.

During the two days before the collapse, 3.72 inches of rain fell on Logan County, enough to push the water within a foot of Dam #3’s crest, which still had no spillway. The situation was precarious, but no warnings were issued. When Dam #3 fell, its toxic contents overwhelmed Dam #2, which also collapsed, followed by Dam #1, sending a wall of water 30-40’ feet high through more than a dozen towns along Buffalo Creek Hollow, home to some 5,000 residents.

Buffalo Creek was one of the worst West Virginia coal mine accidents in terms of lives lost, property destroyed, and damage to the environment. The death toll was 125 people, with over 1,110 injured. More than 500 structures were destroyed, mostly houses but mobile homes and businesses as well. It would be more than 30 years before the fish population that died in the suddenly toxic Buffalo Creek waters would be restocked.

A report by the West Virginia Ad Hoc Commission of Inquiry into the Buffalo Creek Flood concluded the Pittston Company, the parent of Buffalo Mining, “has shown flagrant disregard for the safety of residents of Buffalo Creek and other persons who live near coal-refuse impoundments.” Many of the lawsuits that followed were settled for far less than the original amount. Survivors collectively sued for $64 million and settled for $13.5 million. The state itself sued for $100 million and later settled for $1 million.

Dhanbad, India

The explosion and resulting flood at the Chasnala Mine on Dec. 27, 1975, is one of the worst coal mine disasters in India’s history.

Within the Chasnala colliery was an abandoned mine pit holding approximately 110 million gallons (500,000 m3) of water. Just below the abandoned pit, there was an active pit with hundreds of miners and managers at work. Only a thin wall of coal separated the two. The reported causes of the explosion vary, from sparks igniting methane gas to deliberate operational blasting. In any event, after a period of heavy rain followed by the explosion, the coal wall gave way and released its water onto the workers in the active pit at a rate of about 7 million gallons (32,000 m3) per minute.

It took 26 days to find the first body. The official death toll is given as 372, but the local workers’ union claimed almost 700. With the mine’s records poorly kept and recovery and identification of the victims not always possible, it may never be known. There were no survivors, which is not disputed.

As is often the case, the miners blamed management, management denied responsibility. Four company officials were prosecuted for negligence. The case took 37 years, until 2012, to finally adjudicate. By then, two of the officials had passed away, and the other two were fined 5000 rupees each, about $60 USD at the time.

Cilybebyll, Wales

The Gleision Colliery is a “drift mine” in the Welsh village of Cilybebyll. Drift mines are drilled horizontally into the side of a hill, usually above the water table, and run along the length of the coal bed. The 2011 flood is one of the world’s more significant recent coal mine accidents and one of the worst in Wales’ history.

Similarly to the Chasnala disaster, the colliery had an active mine situated near an unused mine, which was flooded. Seven workers in the active mine were conducting operational blasting and inadvertently connected it to the flooded mine. The active mine started to fill with water, trapping the workers 300 ft (91m) below the surface. Three miners were able to escape, although one had severe injuries. The remains of the four missing workers were found the next day.

The investigation found no safety complaints reported by the miners. Authorities eventually charged the mine manager with manslaughter by gross negligence and the mining company with corporate manslaughter. All parties were eventually acquitted.

Every coal mine accident has safety lessons to offer. Over the years, tighter regulations and technological advances in ventilation, gas and geologic monitoring technology, dust control, communications, automation, and structural support have all improved the overall safety of mining. Personal protective gear and training for miners are now mandated.

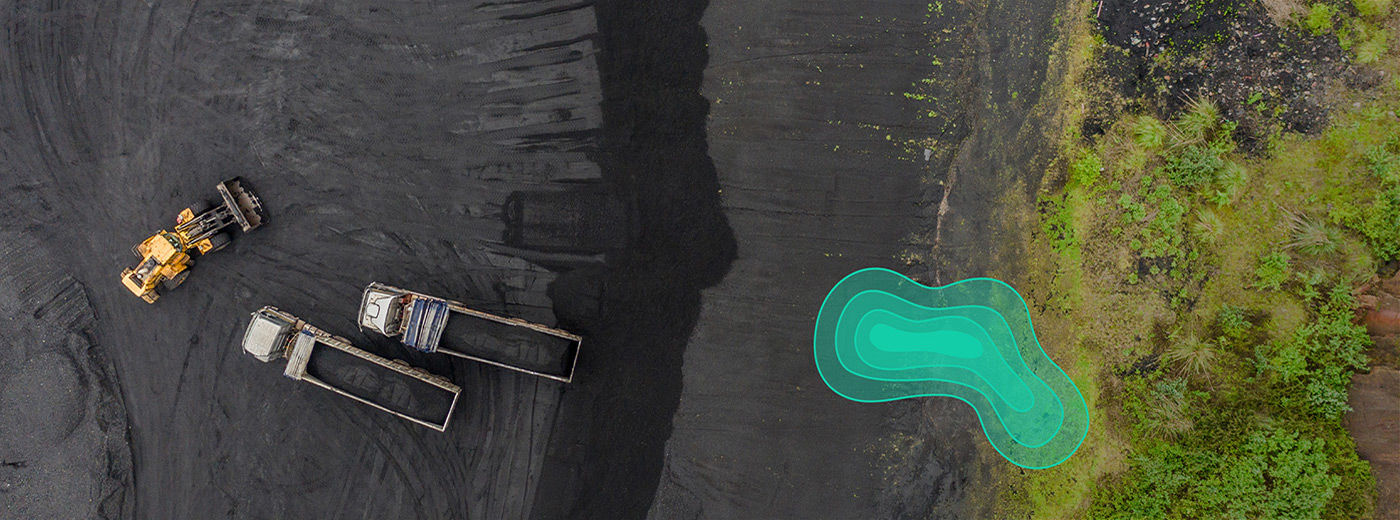

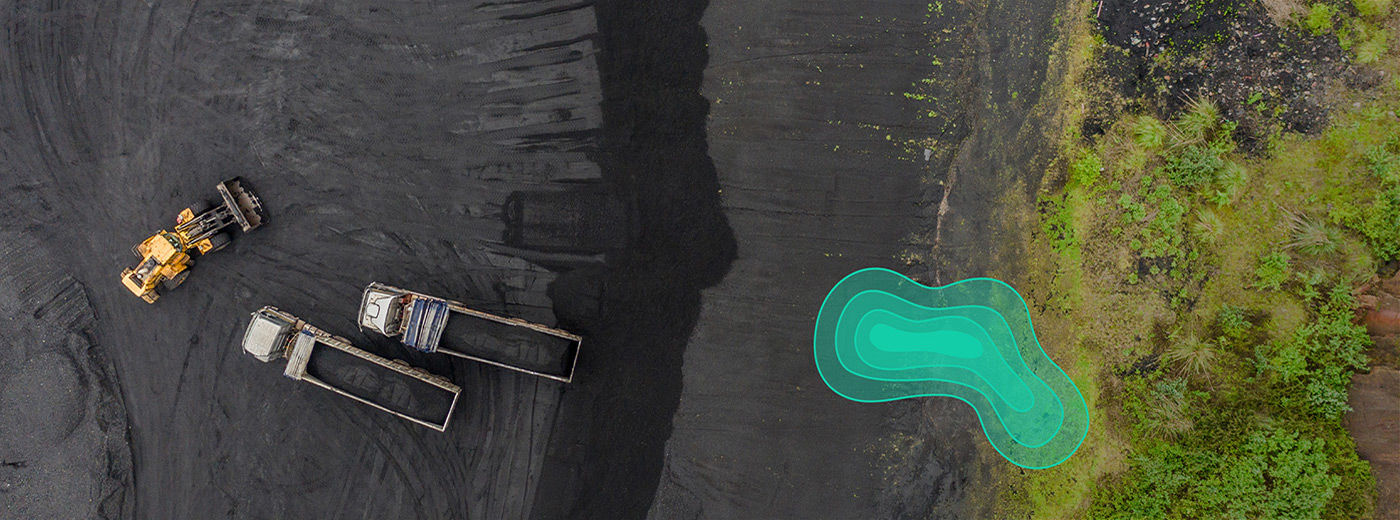

ASTERRA EarthWorks is a recent major advance in satellite-based soil moisture monitoring that’s also making mines and miners safer. Using a band of the radio spectrum that penetrates the soil to approximately 10’ (3m), EarthWorks locates soil moisture that can negatively impact operations, such as soil moisture weakening a mine slope or mine road. It can also locate soil moisture that indicates leakage from an underground conduit.

EarthWorks is especially effective at locating and continually monitoring seepage through earthen tailings dams or water retention dams and provide critical information to prevent failure. EarthWorks even has the ability to issue alerts for critical zones so that decision-makers and engineers can address urgent problems in time to stop them from becoming the next coal mine disaster.

Learn more about ASTERRA EarthWorks and other earth observation technologies.